- Joined

- Oct 19, 2020

- Posts

- 2,988

- Reaction

- 1,289

- Points

- 1,006

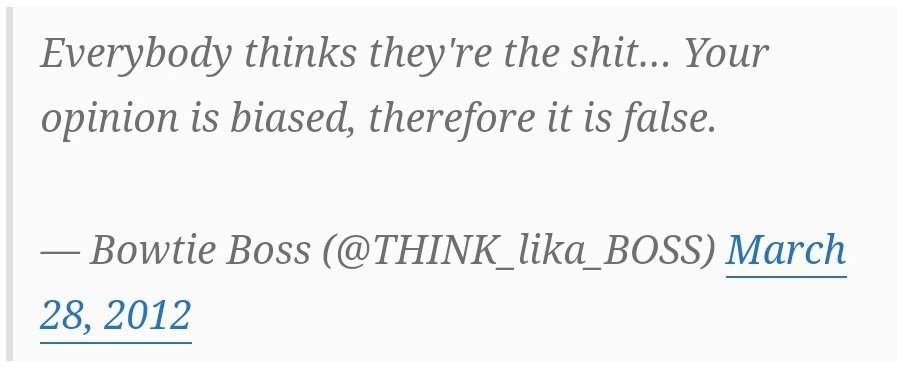

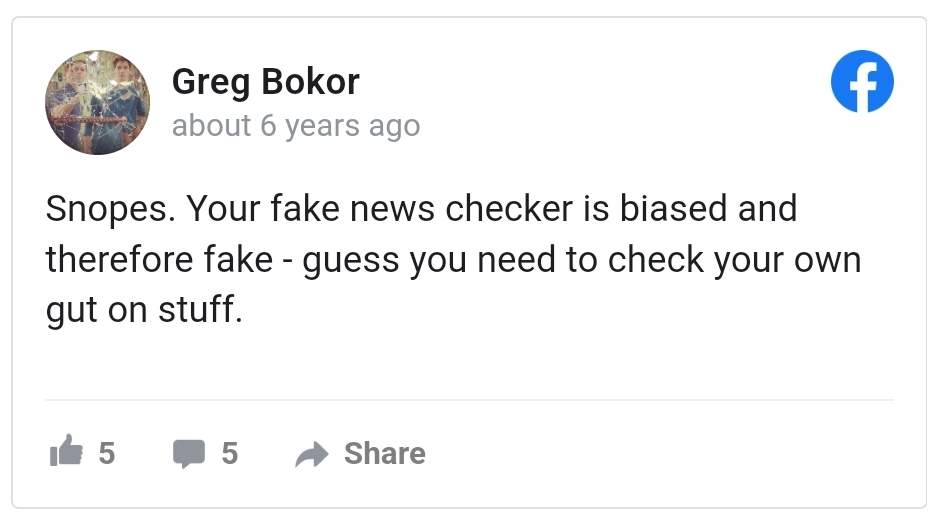

"They’re biased, so they’re wrong!” That’s a fallacy. We can call it the bias fallacy. Here’s why it’s a fallacy: being biased doesn’t entail being wrong. So when someone jumps from the observation that So-and-so is biased to the conclusion that So-and-so is wrong, they commit the bias fallacy. It’s that simple.

In this post, I’ll give some examples of the fallacy, explain the fallacy, and then suggest how we should respond to the bias fallacy.

1. EXAMPLES OF BIAS FALLACY

You’ve probably seen instances of the bias fallacy all over the internet.

In my experience, the fallacy is a rhetorical device. The purpose of the bias fallacy is to dismiss some person or their claims.

Like many rhetorical devices, this one is logically fallacious. So it’s ineffective. At least, it should be ineffective. That is, we should not be persuaded by it.

So if you’ve seen the bias fallacy online, then go ahead and set the record straight:

2. EXPLANATION OF THE BIAS FALLACY

Let me clarify what the bias fallacy is. The bias fallacy has a certain structure. It identifies So-and-so’s bias. And then it infers from the mere existence of So-and-so’s bias to the conclusion that So-and-so is incorrect. So, in its simplest form, the structure of the bias fallacy involves two parts:

So-and-so is biased.

Therefore, So-and-so is wrong.

It is important to notice that the bias fallacy involves a particular inference: inferring falsehood from bias. This relationship is represented by the ‘therefore’ in the example of above. But it might be represented by all sorts of words and phrases in other contexts (e.g., ‘so’, ‘because’, ‘thereby’, etc.).

And that inference is the fallacy. It’s a fallacy because the inference is wrong: falsehood does not necessarily follow from bias. After all, someone can be biased and also be correct. Again, it’s that simple.

But we should be careful here. Take a look at two phrases with a structure that is similar to the bias fallacy. This time, however, the fallacious inference is missing:

So-and-so is biased

So-and-so is wrong.

These claims are entirely independent. So these statements are not saying that So-and-so is wrong because they are biased. So-and-so’s Bias and wrongness can be completely unrelated based on these two claims. So this is not an instance of the bias fallacy.

3. BUT BIASES INCREASES OUR CHANCES OF BEING WRONG, RIGHT?

At this point, you might be thinking that I am merely making some esoteric point that only academics care about. After all, bias is always bad, right? So even if bias doesn’t entail falsehood, it still increases our chances of being wrong…right?

Wrong.

Think about the ways in which someone can be biased. Sure, people can be biased against certain religion, genders, classes, etc. We probably agree that those are bad biases. And those biases can lead to false claims — e.g., false claims about religion, gender, etc. But this doesn’t mean that all biases are bad, that all biases lead to falsehood, or even that all biases increase the chances of being wrong.

Consider medical science. If we want to find out whether smôking causes cancer, then we are going to want to observe peoples’ smôking habits, peoples’ cancer rates, and perhaps some other related variables (e.g., peoples’ exposure to certain kinds of radiation, etc.). But there’s lots of stuff that we do not want to measure. We don’t want to observe people’s music preferences, favorite color, etc. Those variables are irrelevant to the causes of cancer. So good scientific investigation seems to require certain biases. In this case, it was a selection bias: a bias in favor of only relevant evidence.

And this is true more generally: good investigations should involve certain biases.

And, therefore, bias does not necessarily increase the chances of being wrong. In some cases, bias might actually decrease the chances of being wrong.

4. WHAT TO DO ABOUT THE BIAS FALLACY

Imagine that you or someone you know witnesses you committing the bias fallacy. You erroneously inferred that So-and-so is wrong from So-and-so’s bias. What should you do now?

First, acknowledge the fallacy.

Second, acknowledge that it is a fallacy. (And, to be clear, the bias fallacy is usually a certain type of an existing class of fallacies — not a newfound fallacy.)

Third, reflect on the merits and demerits of the claim that you thought was wrong.

That is, consider whether So-and-so is right regardless of their bias(es). Some people are less likely to reflect about that. So some people might have to try harder than others.

But most of us will have to go way out of our way to properly reflect on the matter. We cannot simply go to our friends, family, and usual information outlets. After all, we tend to agree with them. Instead, we have to seek out people and institutions that disagree with us. Those people will be much more motivated to notice the merits and demerits of a claim that we will simply overlook. So until we’ve done the hard work of genuinely considered the perspective of people who disagree with us, we’re in no position to make a good judgment about a claim.

Now let’s say that you’ve done these steps: you’ve admitted the fallacy and done the hard investigative work. So you can now clearly, cogently, and concisely explain why So-and-so’s claim is right or wrong. Now you’re ready for the final step.

Fourth, document your explanation of why So-and-so is right or wrong — so that you don’t have to redo it from memory every time the topic comes up. Better yet, make the explanation public so that others can scrutinize it and — if it passes muster — appreciate it.

5. TAKEAWAYS

Being biased does not entail being wrong. It is possible that someone who is biased is wrong, but they are not necessarily wrong because they are biased. And — more importantly — biased people or institutions are sometimes correct.

So we cannot dismiss the claims of biased people and institutions just because of their bias.

Instead, we have to carefully and thoroughly evaluate claims on a case-by-case basis. And that is no easy feat.

-The Bias Fallacy, by Nick Byrd

In this post, I’ll give some examples of the fallacy, explain the fallacy, and then suggest how we should respond to the bias fallacy.

1. EXAMPLES OF BIAS FALLACY

You’ve probably seen instances of the bias fallacy all over the internet.

In my experience, the fallacy is a rhetorical device. The purpose of the bias fallacy is to dismiss some person or their claims.

Like many rhetorical devices, this one is logically fallacious. So it’s ineffective. At least, it should be ineffective. That is, we should not be persuaded by it.

So if you’ve seen the bias fallacy online, then go ahead and set the record straight:

2. EXPLANATION OF THE BIAS FALLACY

Let me clarify what the bias fallacy is. The bias fallacy has a certain structure. It identifies So-and-so’s bias. And then it infers from the mere existence of So-and-so’s bias to the conclusion that So-and-so is incorrect. So, in its simplest form, the structure of the bias fallacy involves two parts:

So-and-so is biased.

Therefore, So-and-so is wrong.

It is important to notice that the bias fallacy involves a particular inference: inferring falsehood from bias. This relationship is represented by the ‘therefore’ in the example of above. But it might be represented by all sorts of words and phrases in other contexts (e.g., ‘so’, ‘because’, ‘thereby’, etc.).

And that inference is the fallacy. It’s a fallacy because the inference is wrong: falsehood does not necessarily follow from bias. After all, someone can be biased and also be correct. Again, it’s that simple.

But we should be careful here. Take a look at two phrases with a structure that is similar to the bias fallacy. This time, however, the fallacious inference is missing:

So-and-so is biased

So-and-so is wrong.

These claims are entirely independent. So these statements are not saying that So-and-so is wrong because they are biased. So-and-so’s Bias and wrongness can be completely unrelated based on these two claims. So this is not an instance of the bias fallacy.

3. BUT BIASES INCREASES OUR CHANCES OF BEING WRONG, RIGHT?

At this point, you might be thinking that I am merely making some esoteric point that only academics care about. After all, bias is always bad, right? So even if bias doesn’t entail falsehood, it still increases our chances of being wrong…right?

Wrong.

Think about the ways in which someone can be biased. Sure, people can be biased against certain religion, genders, classes, etc. We probably agree that those are bad biases. And those biases can lead to false claims — e.g., false claims about religion, gender, etc. But this doesn’t mean that all biases are bad, that all biases lead to falsehood, or even that all biases increase the chances of being wrong.

Consider medical science. If we want to find out whether smôking causes cancer, then we are going to want to observe peoples’ smôking habits, peoples’ cancer rates, and perhaps some other related variables (e.g., peoples’ exposure to certain kinds of radiation, etc.). But there’s lots of stuff that we do not want to measure. We don’t want to observe people’s music preferences, favorite color, etc. Those variables are irrelevant to the causes of cancer. So good scientific investigation seems to require certain biases. In this case, it was a selection bias: a bias in favor of only relevant evidence.

And this is true more generally: good investigations should involve certain biases.

And, therefore, bias does not necessarily increase the chances of being wrong. In some cases, bias might actually decrease the chances of being wrong.

4. WHAT TO DO ABOUT THE BIAS FALLACY

Imagine that you or someone you know witnesses you committing the bias fallacy. You erroneously inferred that So-and-so is wrong from So-and-so’s bias. What should you do now?

First, acknowledge the fallacy.

Second, acknowledge that it is a fallacy. (And, to be clear, the bias fallacy is usually a certain type of an existing class of fallacies — not a newfound fallacy.)

Third, reflect on the merits and demerits of the claim that you thought was wrong.

That is, consider whether So-and-so is right regardless of their bias(es). Some people are less likely to reflect about that. So some people might have to try harder than others.

But most of us will have to go way out of our way to properly reflect on the matter. We cannot simply go to our friends, family, and usual information outlets. After all, we tend to agree with them. Instead, we have to seek out people and institutions that disagree with us. Those people will be much more motivated to notice the merits and demerits of a claim that we will simply overlook. So until we’ve done the hard work of genuinely considered the perspective of people who disagree with us, we’re in no position to make a good judgment about a claim.

Now let’s say that you’ve done these steps: you’ve admitted the fallacy and done the hard investigative work. So you can now clearly, cogently, and concisely explain why So-and-so’s claim is right or wrong. Now you’re ready for the final step.

Fourth, document your explanation of why So-and-so is right or wrong — so that you don’t have to redo it from memory every time the topic comes up. Better yet, make the explanation public so that others can scrutinize it and — if it passes muster — appreciate it.

5. TAKEAWAYS

Being biased does not entail being wrong. It is possible that someone who is biased is wrong, but they are not necessarily wrong because they are biased. And — more importantly — biased people or institutions are sometimes correct.

So we cannot dismiss the claims of biased people and institutions just because of their bias.

Instead, we have to carefully and thoroughly evaluate claims on a case-by-case basis. And that is no easy feat.

-The Bias Fallacy, by Nick Byrd

Attachments

-

You do not have permission to view the full content of this post. Log in or register now.